|

The Great Influenza by John M. Barry is 15-year old book that all-of-a-sudden skyrocketed back into Amazon's Top 100 for reasons that should be pretty obvious. The book tells the haunting story of the most deadly pandemic in world history; The Spanish Flu. By its higher estimates, that flu killed more people than World War I and II combined along with every person who's died in a war the United States has fought in on both sides! Estimates for the pandemic range from 50 to 100 million in all. The book is effectively broken into three parts. The first part deals with the development of medical science in the United States, which had previously lagged behind Europe. Indeed, medical science in general had lagged behind pretty much every other field of science and, by the mid-nineteenth century, still hadn't progressed much beyond Hippocrates. Doctors were even still bleeding people as a "cure" into the twentieth century! Indeed, as Nassim Nicholas Taleb noted in his excellent book AntiFragile, prior to the invention of antibiotics, it was usually more dangerous to go to a hospital than to just stay home with whatever illness you had acquired! Fortunately, medicine was finally starting to see dramatic improvements by the late nineteenth century. The first chapter starts with the opening of John Hopkins University where "They planned to change the way which Americans tried to understand and grapple with nature." The story then follows William Welch and his way up to the top of John Hopkins as well as many other American scientists at the dawn of American medical science; such as Paul Lewis, William Park, Anna Williams and Oswald Avery. The final section deals with the aftermath, including Oswald Avery's discoveries which became the key step toward Watson and Crick's discovery of DNA. It also notes that Alexander Fleming discovered Penicillin while working to verify what caused the Spanish Flu in the early 20's. In between these two sections of interesting history is a middle section whose genre could best be described as horror. Unfortunately, those scientists the book spent its first 150 or so pages discussing could do little to stem the tide of this monster. Antibiotics hadn't been invented yet and few effective vaccines against diseases and none against the flu, especially this one. Some doctors tried to create and administer vaccines during the pandemic, but they were ineffective. Plasma serums had been invented, but given how difficult they are to produce (the plasma must be taken from someone who has recovered from the illness), they didn't help much overall.

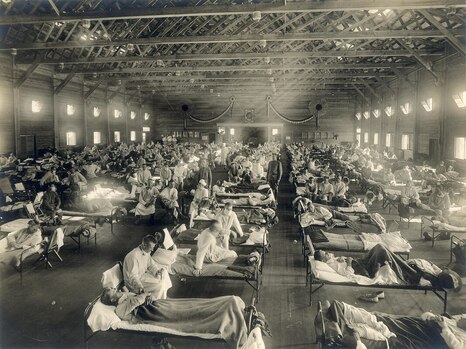

The pandemic appears to have started about 350 miles from where I currently sit; in the small town of Haskell, Kansas. (There are other theories, including China and France, but Haskell is the leading one.) There it would have likely stayed had it not been for Woodrow Wilson's disastrous decision to bring the United States into the First World War. One newly drafted soldier left Haskell to Fort Riley and likely brought with him a novel virus that was about to set the world on fire. Shortly thereafter, a huge number of soldiers at Fort Riley got sick. But fortunately for them, this was during the relatively mild first wave in the Summer of 1918. Almost all of them survived. Unfortunately, the virus later mutated and came back with an unprecedented vengeance in September of 1918. It really got started in Camp Devens, where something like half of the troops stationed there got sick, soldiers died like flies and the camp commander ended up committing suicide. And unlike most influenza viruses, this one was most deadly to those between the ages of 25 and 35. The reason was that their immune systems were the strongest and by engaging their enemy with such force, their immune systems actually took the whole body down with the virus in what is known as a cytokine storm. Thus, the Spanish Flu had a W-shaped fatality curve. The very young and very old died the most (often from secondary, bacterial infections that lead to pneumonia), but the young were right behind them. About half of American troops who died in World War I were from the Spanish Flu. The disease went wild from military camp to military camp before spreading to the cities; most notably New York and Philadelphia. In a oft-given example, Philadelphia foolishly decided to hold its annual parade whereas St. Louis cancelled their's. St. Louis survived relatively unscathed. Philadelphia descended into chaos. "Someone was sick in every house," Barry notes. The death rate on a single day doubled the average death rate per week in the city. Hospitals were wildly overcrowded and had to turn away patients. They were also horribly short-staffed and it only became worse when the doctors and nurses got sick too and even worse still when many of those doctors and nurses died. The hospitals begged for volunteers, but few came. Everyone was frightened to leave their house. Some feared that "civilization itself was ending." The situation with the military was even worse and utterly unconscionable. While today, our government has, in my humble opinion, gone overboard with the lockdown and precautions, in 1918, the federal government did nothing. And by that, I mean they did very close to absolutely nothing. Wilson never made a single public statement on the matter. And the only known private discussion had to do with troop transports and whether or not to halt them. They decided to keep them going and these ships became floating coffins. On some, close to half the soldiers died. I should also note that this was in October and November of 1918. The war ended on November 11th, 1918. When this decision was made, the German military was collapsing and an Entente victory was inevitable. Wilson's decision was, for the second time, utterly indefensible. Wilson also appears to have gotten the Spanish Flu during its third wave at the beginning of 1919. Many have said it was a stroke, but it appears to have just been the flu. He survived, but strangely gave into the vicious demands of the British and French against the Germans that lead to the vindictive Treaty of Versailles and created the resentment the Nazis would later capitalize on. The contrast between then and now could not be more stark. It's amazing that our government today would shut down the economy and throw the country into a deep recession (and possibly depression) for a virus that has killed (as of this writing) 340,000 people worldwide. Whereas in 1918, the federal government did close to nothing for a virus that killed as many as 100 million. Then United States didn't even suffer a recession! It's as if these two responses, separated by over 100 years, make up the extremes for awful responses to a global pandemic. Reading the book, I was also reminded of the recent, excellently made Chernobyl miniseries. I would recommend the makers of that show pick up the rights to The Great Influenza and begin filming a similar miniseries right away. It would be great, topical and feel quite similar to Chernobyl. Indeed, it's all the more fitting as our government did about as well in 1918 as the Soviets did with Chernobyl. Furthermore, much of that show came off as a horror movie. A miniseries on The Great Influenza would feel the same. The book also made me feel better about the Coronavirus. Don't get me wrong, Covid-19 is still a serious issue and many have died. There also might be another wave. But from what I've seen so far, this pandemic isn't even close to what Barry describes. (Especially as there have been many stories of furloughed or laid off healthcare workers in the middle of this outbreak.) While the Coronavirus pandemic will be far worse than the Swine Flu pandemic, unless it drastically mutates, it won't come anywhere close to the Spanish Flu pandemic. The Great Influenza is highly engaging and I flew through it despite its considerable length of some 450 pages. My only complaint is that it focuses almost exclusively on the United States and only gives scant mention to what happened abroad. 50 to 100 million died worldwide, while "only" 650,000 of those deaths occurred in the United States. India, for example, was hit particularly bad. I would have preferred to hear more about what happened in many other parts of the world, particularly on the Western Front as the war came to a close. That being said, at 450 pages there was probably just no space for a further discussion of what happened elsewhere. That would the topic for another book. As for the topic of the Spanish Flu in the United States, The Great Influenza makes for a great read.

Comments

|

Andrew Syrios"Every day is a new life to the wise man." Archives

August 2018

Blog Roll

Bigger Pockets REI Club Tim Ferris Joe Rogan Adam Carolla MAREI Worcester Investments Entrepreneur The Righteous Mind Star Slate Codex Mises Institute Tom Woods Consulting by RPM Swift Economics Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed