|

I seriously may need to make a series offering a does of sanity to those with Trump Derangement Syndrome who are suffering unhinged overreactions over the current administration. So Trump criticized the Fed's decision to raise the Federal Funds rate and of course, the "this is not normal!" chorus of blue checkmarks started going again. This was basically par for the course:

How dare Trump criticize an institution that was planned in secret, passed on just before Christmas Eve, caused or at least deepened the Great Depression and Great Recession for that matter and refuses any sort of real audit? How dare he!

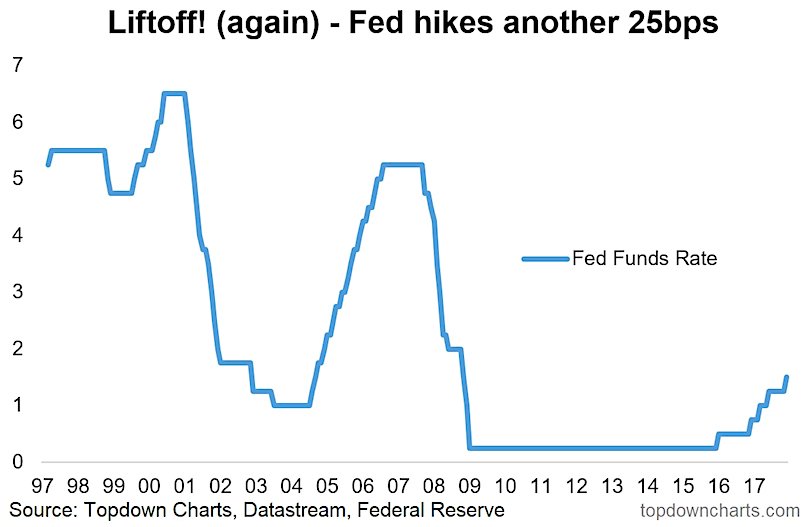

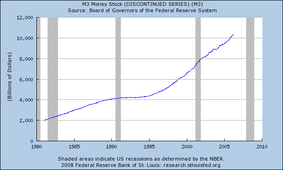

And yeah, while the economy is hot (4.1 percent growth last quarter) and may need cooled off, this chart does look just a wee bit suspicious:

But let's set aside the conspiracy theories. As far as the "this is not normal!" hysteria from the Left regarding Trump and the Fed, well, a better way to put it is "this is rather mundane." Former Congressman Ron Paul reminds us of a slightly more egregious case "political interference" with the Fed,

"When it comes to intimidating the Federal Reserve, President Trump pales in comparison to President Lyndon Johnson. After the Federal Reserve increased interest rates in 1965, President Johnson summoned then-Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin to Johnson’s Texas ranch where Johnson shoved him against the wall. Physically assaulting the Fed chairman is probably a greater threat to Federal Reserve independence than questioning the Fed’s policies on Twitter." But "muh this is not normal!" or whatever...

Comments

This is an old article on the 2008 financial crash that I wrote for Swifteconomics, which is now sadly defunct, that I would like to repost here. Hope you enjoy: In 1759, Voltaire wrote his satirical, Magnum Opus, Candide, eponymously named after the main character, who after leading a sheltered life for many years, comes to the realization that all is not right in the world, and we must do our best to improve it. This is in direct contradiction to his mentor, Pangloss, whose mantra is “all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.” In other words, we are already living in a utopia, it simply cannot get any better, which he humorously (albeit darkly) explains to someone who just lost his whole family after an earthquake. The idea that war has a good side effect reminds me of the Leibnizian optimism (everything happens for the best) that Voltaire so thoroughly refuted. Some things, such as war, may be necessary, but they are in no way good, and have no silver lining. War is horrible… but it’s good for the economy. I cannot, for the life of me, think of a more dangerous myth than that. This facade has become so prevalent in the national conscience that it’s simply taken for granted. The reasoning for this myth comes from an offshoot of Keynesian economics, in summary it says war stimulates aggregate demand and thereby gets the wheels of the economy turning again (or turning faster). The key piece of evidence used for this assertion is World War II, which is arrogantly claimed, over and over again, to have ended the Great Depression. As MSN Encarta so helpfully informs us, “the depression ended in the United States only when massive spending for World War II began.” Seriously though, why would anyone actually believe this without at least a little skepticism? Wars are enormously destructive and shift resources from human needs, to human destruction. The key problem with the theory itself, is that such stimulus, military or otherwise, relies on government spending. The government doesn’t have anything except what it takes, it can do little more than shuffle the deck. Government can tax the population, inflate the currency (another tax) or borrow the money (a deferred tax). Deficits are usually the prescribed course of action, but if you borrow from your own citizens then you’ve simply used up capital that could have been borrowed by private citizens and companies anyways. This is especially true for domestic borrowing, but is also the case with borrowing from abroad. Regardless, as the government borrows more, the reduced supply of available capital will raise interest rates for everyone else. Admittedly, this may provide short-term growth, if investor confidence is low, but such a prescription has long-term consequences, as the debt has to be repaid with interest. And as with the United States, we’re already up to our eyeballs in debt. Furthermore, these benefits are only accrued if that money is spent on projects of economic value. Wars do not provide any economic value. Keynesian economics can be discussed at further length another time; I’ll instead focus the rest of this article on the conspicuously lonely example proving the splendors of “military-Keynesianism.” So let’s get to World War II. First of all, it’s obvious that conquest can help an economy in some cases. When the Soviet Union colonized Eastern Europe after World War II, their population, and supply of capital, vastly grew, which is obviously good for an economy. However, that’s simply saying that theft makes one richer. Not really the most provocative insight there. But what we’re discussing here is does the act of war itself stimulate an economy? Let’s for a moment assume that the popular fable behind World War II is correct. War is what got the United States out of the Depression. Okay, who cares? There’s one example of war stimulating an economy…Check that, there’s one example inside of a larger example that illustrates the exact opposite. Everything else points toward war having dire economic consequence. After World War II, Britain was basically bankrupt and had to liquidate their empire. Same goes for France. Germany, Japan and Italy were burnt to the ground. China was a train wreck before and an even bigger train wreck afterward. World War II only “worked” for the United States. Furthermore look at the rest of the wars our species has, unfortunately, had to endure. The United States went into a severe recession in 1920, just after World War I. Germany’s currency hyperinflated while the Austrian, Ottoman and Russian Empires simply collapsed. In the American Civil War, the South was reduced to rubble and the North suffered runaway inflation. After the Revolutionary War, the American currency hyperinflated (thus the saying “not worth a Continental”). Rome’s collapse was mostly due to corruption at home and military over extension abroad. Napoleon was so strapped for money after the early stages of the Napoleonic War, he had to sell the Louisiana territories to the United States for pennies on the dollar. The Franco-Prussian War was almost immediately followed by a speculative housing bust, which created the panic of 1873 and a global depression. Spain was more or less left to the ash bin of history, after the Spanish Armada was destroyed (shouldn’t there have been an enormous economic stimulus to rebuild?). The combination of spending on the Vietnam War and the Great Society lead to the stagflation of the 1970’s. In addition, the United States suffered recessions immediately following the Korean War, Gulf War and Serbian War. The Soviet Union collapsed after a long war in Afghanistan. Honestly, have the many sub-Saharan wars in Africa stimulated their economies? Has this economic strategy worked for Middle Eastern countries bogged down in decades of conflict? And really, if war is so good for an economy, why is our own economy collapsing all around us, while we are engaged in outrageously expensive boondoggles in Iraq and Afghanistan? Now correlation does not equal causation; not all the previously mentioned wars were completely, or even mostly responsible, for the corresponding economic upheavals. Regardless, it’s worth noting that I have about a thousand data points to make a trend, and the standard “wisdom” has but one outlier. Well one outlier proves absolutely nothing, so the burden of proof lies not with me, but with the standard “wisdom.” I should be able to end this article victoriously right here, but I feel it’s important to note, that upon closer analysis, even this one outlier is nothing of the sort. Economic historian Robert Higgs’ work on this subject is simply unparalleled; if you are interested in a more detailed analysis of this issue, see his book Depression, War and Cold War or an overview here. Simply put, the case for World War II getting the United States out of the Depression, primarily lies with two statistics: 1) unemployment went from around 10% to almost nothing and 2) GDP skyrocketed upwards. We’ll start with unemployment, according to Robert Higgs: “What actually happened was no mystery. In 1940, before the mobilization [for war], the unemployment rate … was 9.5 percent. During the war, the government pulled the equivalent of 22 percent of the prewar labor force into the armed forces. Voilà – the unemployment rate dropped to a very low level.” (1) Yes, unemployment went down, but that’s because we shipped millions of young men overseas. We could have kept them in the United States and reduced unemployment by having them dig holes in the ground. Or we could have put them in prison, or just shot them. All these things would reduce the supply of labor, and thereby bring the number of jobs and workers back into equilibrium. This sort of strategy has consequences though. What really happened during the war was the way the Depression affected the American people changed. The main problem during the Depression was deflation; between 1929 and 1932 one third of the money in circulation disappeared. Yet the government, (both Hoover and Roosevelt) tried to prop up wages and prices. This, predictably, caused massive unemployment, since there wasn’t enough money available to pay people their previous wages. Back in the 1930’s there was a saying that “the Depression was not so bad if you had a job” which makes perfect sense, since wages were kept artificially high. (2) During the war, the situation reversed itself. Just about everyone had a job, but the standard of living was drastically reduced. Price controls, rationing and shortages became commonplace. Housing starts stopped. Entire lines of products, such as steel, were off limits to the public. Now, instead of the unemployed feeling a lot of pain, everyone felt some pain. As far as GDP goes, the statistics say the United States grew a total of almost 35% between 1941 and 1945. However, the United States had what could best be described as a command economy during the war. In other words, economic decisions for the whole country were made from the White House. The government set the prices for most goods (and rapidly inflated the money supply) so these GDP figures are all but useless. According to GDP statistics, if the government pays $100 for a hammer instead of $10, the economy gains $90. But that really doesn’t tell us anything about overall economic health. All it would tell us is the government wasted $90. As far as private production goes, things were not good at all. Turning again to Robert Higgs: “…from 1941 to 1943, real gross private domestic investment plunged by 64 percent; during the four years of the war, it never rose above 55 percent of its 1941 level [and] only in 1946 did it reach a new high.” (3) To further prove this point, we simply have to look at the end of the war, when the United States started to demobilize. The GDP decreased 20.6% in 1946 alone! This should be recorded as one of the worst years in economic history. However, 1946 saw extraordinary gains in the private sector that have never been repeated since. (4) So what ended the depression? Well, the fact that the United States was, more or less, the only country left standing after the war may have helped by putting our exports in high demand. However, this has nothing to do with war itself and trying to repeat this strategy to fix our current crisis seems to me just a bit, well a bit unethical. According to Robert Higgs, the actual key was the end to what he called “regime uncertainty.” In the later parts of the New Deal, the Roosevelt administration’s behavior had become unpredictable and many businesspeople were scared to invest. This was amplified during World War II, when much of the economy was simply taken over by the government. However, after the war ended, there was, to borrow a phrase from Warren Harding, a return to normalcy. The uncertainty was more or less over and people could, once again, pursue their personal interests in relative peace. This was what likely got the gears of the economy moving again and finally ended the Great Depression.

But again, even if professor Higgs and laymen, like myself, are wrong, we are only wrong about one example within an example. The rest of the trend points safely in our direction. It’s also important to note that the burdens of war go on for many years after a war has ended. Completely ignoring the tragic human cost, the overall economy suffers as many soldiers are left wounded and can no longer work or work as productively as they could, before their service. A significant amount of money has to be spent to take care of injured soldiers as well. The Department of Veterans Affairs requested $93.7 billion dollars for 2009. These costs continue year after year. Even today, we see the heart-wrenching scene of disabled Vietnam veterans begging for money on street corners. Decades from now, we may, unfortunately, see the same from veterans of the war in Iraq, who could have lead quite productive lives, if they hadn’t been scarred by war. Even the simple act of diverting resources away from the productive sector of the economy, into the military is costly. While being a soldier is a very honorable profession, it doesn’t produce much of economic worth. When the military becomes bogged down in a war, we transfer many resources from the production of consumer goods, to a war that is usually thousands of miles from our shores. And this doesn’t only happen in wartime, as the United States currently has about 700 military bases in 130 countries; all of which cost money without providing any sort of economic stimulus. So war may improve artificially inflated GDP figures, temporarily reduce unemployment and even provide a short-term economic boost, it does not, however, stimulate the economy in any meaningful long-term sense. Quite to the contrary, Voltaire was right, Pangloss was wrong, and war often leads to economic disaster. In addition, the negative effects of wars, both economic and social, linger for years. Perhaps they linger just until we forget about them, so we can then repeat the same mistakes all over again. After all, the only thing we seem to learn from history, is that we don’t learn from history. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ (1) Quoted in Anthony Gregory, "The Myth of War Prosperity," LewRockwell.com, April 3, 2007, Future of Freedom Foundation, Copyright 2007, http://www.lewrockwell.com/gregory/gregory132.html (2) See Amity Shlaes, The Forgotten Man, Pg. 9, HarperCollins Publishers, Copyright 2007 (3) Quoted in Anthony Gregory, "The Myth of War Prosperity," LewRockwell.com, April 3, 2007, Future of Freedom Foundation, Copyright 2007, http://www.lewrockwell.com/gregory/gregory132.html (4) Ibid The following is a Graduate paper I wrote on creativity and how the definition of that word has changed for me. It also discusses several creative techniques including Empathic Design, The Young Technique and the SCAMPER method as well as how our team applied those techniques to coming up with possible entrepreneurial ventures. I think it will be helpful for those who are trying to discover how to become more creative. The word “creativity” seemed to be one of those words that had such a simple meaning it didn’t merit further reflection. The word had little more interest to me than words such as “smart” or “strong” or “courageous” did. Creativity was obviously an important concept, but it’s definition seemed self-evident. Dictionary.com defines “creativity” as follows, “The ability to transcend traditional ideas, rules, patterns, relationships, or the like, and to create meaningful new ideas, forms, methods, interpretations, etc.; originality, progressiveness, or imagination.” And that is pretty much what I saw it as. Indeed, “ability” is probably the key word there. Creativity was an ability; something you either had or you didn’t. So for example, musicians are creative people. And I had more or less bought into the stereotype of the creative musician who just comes up with material or “feels” what kind of music to write. Creativity was thus, in my mind, something of a free-floating, ethereal thing that inspired creative works. The definition I had in my mind was something close to circular reasoning; creative people get inspired by creative ideas in order to be creative. Perhaps deep down I knew this was false. For example, I was well aware of how important brainstorming was. And I also knew that brainstorming was done best when ideas weren’t judged immediately. This process gave people the space to throw out off-the-wall ideas that might sound stupid (and otherwise be shot down right away if ever said at all). And while those off-the-wall ideas might indeed be stupid, they may also have a nugget of genius in them that can be built off in all sorts of creative directions. In other words, somewhere deep down I knew that creativity could be a process, but I hadn’t put enough thought into it to really embrace that idea. This class has helped me realize that creativity is not just some form of divine inspiration that is bestowed upon those lucky enough to be born “creative.” Some people may naturally be more creative than others, but regardless of any inborn predispositions, when people funnel the goal of coming up with new ideas, products, services or the like through an effective process, anyone can become more creative. This really rung true to me when watching a short video of Jerry Seinfeld talking about how he comes up with a joke. Most people probably think that standup comics are just funny people who think of funny things because they are so funny and creative. Perhaps that’s because, as Seinfeld notes, “Comedy writing is something you don’t see people doing. It’s a secretive thing.” In some ways, those who are successfully able to be creative appear to enjoy the perpetuating behind their creativity that myself and many others have bought into. Seinfeld’s process, however, proves that conception to be utterly false. For example, he notes all sorts of specific things he tries to do when going through his process of writing a joke, including:

This simple idea; that creativity could and should be funneled through a process was by far the most important take away I had. In this class we went over 16 different processes by which to be creative, such as SCAMPER, The Young Technique and User-Centered Design. To be honest, I had no idea that any of these existed before. However, when reflecting on this, I realized that I should have known such processes existed. For example, I was aware that 3M had come up with the extremely useful and profitable Post-It Note by simply allocating a percentage of each employee’s day to work on ideas they came up with independently. (3) This isn’t much of a process, but at least at the corporate level, it’s something more than the myth that creativity is just “ideas randomly coming to you” or something to that effect. The process that I was assigned was Empathic Design, which was first articulated by Dorothy Leonard and Jeffrey Rayport in The Harvard Business Review and which the design firm IDEO has made famous (albeit with some modifications). The process follows a simple five steps:

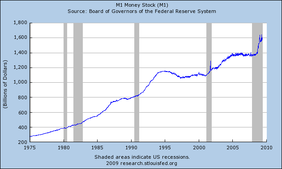

The key behind this method is that by observing how customers actually use a product, you can spot what they actually need instead of what they think they need. Indeed, when it comes to innovation, customers often don’t know what would help them because such a thing doesn’t exist yet (or hasn’t been marketed for that function). One example Leonard and Sax give is of Cheerios. Brand executives learned that parents liked their product so much not because it was a good breakfast cereal, but because it was an easy snack to carry around for their kids. This provided them with a great marketing opportunity they would have otherwise missed. And even if that idea had just floated into someone’s head, how would have they tested it to make sure it was correct without some sort of process to funnel creativity through? Many of the other techniques also appeared to be effective. For example, one idea I had for the final project that we eventually rejected was a built-in mattress alarm. Basically, the alarm would go off until you got out of bed. We applied The Young Technique, which involves putting the idea to the side for a while until it naturally comes back to you. When this idea came back, it became clear that the alarm would be better as a sort of pad that went under the mattress instead of being built into the mattress. For one, that would mean the product was transportable and also, it would make it so the product could be sold on its own without either 1) going into the mattress business or 2) getting some sort of contract with a mattress firm. Sometimes, I had usedparts of these processes without even realizing it. For example, with regards to the concept we eventually decided upon for this class’ final project, I effectively used the SCAMPER method without realizing it. The SCAMPER method is all about substituting, combining and modifying an already existing product in ways that could either improve the product or make something new altogether. In this case, it was with regards to combing the concept of crowdfunding–particularly microcredit–with payday loans. Payday loans are infamous for their high rates of interest. Including fees, the APR on a loan is around 400 percent! But if payday loans could be combined with crowdsourcing in a way similar to KIVA.org (which crowdsources small loans for entrepreneurs in the developing world), such debts could be incurred with no interest at all. All that would be required would be for charities, philanthropists or government grants to pick up the operating costs. That being said, while I used parts of the SCAMPER method by accident in that case, it has become clear that when taking on a project that requires creativity, it is far superior to consciously use a creative process to funnel that energy through than to simply wing it. That key concept along with the elaborations of many such creative processes is the key difference between how I saw and how I now see creativity. This is an old article on the 2008 financial crash that I wrote for Swifteconomics.com, which is now sadly defunct, that I would like to repost here. Hope you enjoy: In the first part of my series on the financial crisis, we discovered that by loosening regulations on the housing industry, while simultaneously continuing to federally back deposits and bailout banks in case anything went wrong, the government created an ample playground for massive speculation. In this second part, we will look at why that speculation was focused in real estate, and where the money to fund such speculation came from in the first place. We’ll start with the question: “Why housing?” It starts with a redefinition of the American Dream. Whereas in years past, the American dream was best defined as prosperity can be found in liberty, it has become, in modern times, that home ownership is the key ingredient to achieving such a dream. As George Bush’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Alphonso Jackson put bluntly, “The American dream is to own a home.” This paradigm dates back to the New Deal. Before the New Deal, owning a home was not as important as it is today, because housing prices were relatively stable and even declined over the years. However, during the Great Depression, political radicalism became common place. In 1928, the Communist and Socialist parties garnered a combined 300,000 votes. In 1932, they received almost a million. (1) In an effort to stabilize the mortgage industry, and hedge off political radicalism, FDR and his brain trust decided to push for home ownership in the United States. They believed a property-owning citizenry would have a greater stake in the Republic and be less prone to revolutionary ideas. This culminated in the creation of Fannie Mae (and later Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae). Fannie Mae works by buying mortgages directly from banks, thus freeing up capital for banks to make more home loans, thus creating more homeowners and fewer renters. And as a result, as economic historian Niall Ferguson puts it, the “property-owning democracy” was born. However, as nice as owning your home sounds, it is a poor, long term investment financially speaking, unless one has other assets with which to compliment it. In general, buying real estate to use as rental properties is a good investment. On the other hand though, piling a large percentage of one’s income into a home that provides no return outside of appreciation, puts all of one’s proverbial eggs in one proverbial basket. If the local housing market depreciates, a major portion of one’s wealth is affected. Every finance professor stresses the importance of diversification. The idea is to hedge the risk of certain companies and industries against as many other companies and industries as possible. By spreading one’s nest egg so thinly, if one company fails or a particular industry has a rough year, the overall portfolio is relatively unaffected. This is why most unseasoned investors put their money in mutual funds, 401K’s and IRA’s. These instruments are designed specifically to hedge clients against risk by investing in a large number of stable companies across a vast array of industries. This concept was, unfortunately, completely forgotten with regards to housing. And as the trumpeters for home ownership grew louder and louder, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae jumped on every opportunity they could to increase the availability of credit to homeowners. Their primary method was a process called securitization. In short, these government supported entities (GSE’s) could slice and dice a whole array of mortgages into mortgage backed securities and sell them off in little chunks to other investors (these investors are all over the world, which is one of the main reasons this crisis, which originated in the United States, is being felt worldwide). A few attempts were made to regulate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but Congressional Democrats, lead by Barney Frank and Chris Dodd (who received more campaign funds from Fannie Mae than any other politician), would have none of it. As Democratic Congresswoman Maxine Waters, last seen on this blog trying to establish a Soviet Commissar to nationalize the entire oil industry, put it in a 2004 congressional hearing: “[We’ve been] through nearly a dozen hearings, where frankly, we were trying to fix something that wasn’t broke. Mr. Chairman, we do not have a crisis at Freddie Mac, and particularly at Fannie Mae, under the outstanding leadership of Mr. Frank Raines.” (2) Four years later the government had to nationalize both Freddie and Fannie. Good call Maxine. Regardless, as these GSE’s began slicing, dicing and selling mortgages off unimpeded, Wall Street decided to get their dirty hands in on the mess. With home prices rapidly increasing and an enormous influx of capital (to be discussed later), banks wanted to capitalize on this new financial instrument (the mortgage backed security). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac started securitizing sub-prime and Alt-A mortgages in 1999, and major banks were particularly interested in going after this market as well. These borrowers usually had bad credit and little if anything to put down on a property. So Wall Street firms followed in Fannie Mae’s footsteps by piling large collections of these risky mortgages together and selling little pieces of them off to the general public. They thereby created a high yield investment vehicle that supposedly reduced risk by dividing the many mortgages up so thinly. Unfortunately, this only hedged against individual defaults or local downturns. It completely ignored the possibility that there was a systemic problem within the real estate market as a whole. In the words of Peter Schiff, who saw the crisis coming as early as 2002: “By creating a conflict of interest between the real estate market and mortgage market, securitization has corrupted an industry in which the availability and cost of credit are of central economic importance.” (3) Furthermore, the incredible complexity of these instruments made them almost impossible to value properly. To paraphrase Niall Ferguson, “instead of risk being transferred to those best able to bare it, risk was transferred to those least able to understand it.” Fannie, Freddie and Ginnie were not the only culprits, though. In the late 1990’s, the Clinton Administration put an extreme emphasis on increasing home ownership. Aside from giving the previously mentioned GSE’s more leeway, they also started vigorously enforcing everything they could find, or create, to increase home ownership. One of the most prominent was the Community Reinvestment Act, originally passed during the Carter Administration. The Community Reinvestment Act was originally passed with the intent to increase lending to minorities and end the discriminatory practice known as redlining (basically, banks wouldn’t lend to neighborhoods with large minority populations). Unfortunately, as these things often go, it went from one extreme to another, and the opposite of one crazy is still crazy. Instead of blacklisting minority applicants, in the 1990’s and 2000’s, banks were scared to death of lawsuits from declining mortgages to minorities or low-income folks, even if those particular people weren’t financially capable of meeting their mortgage obligations. Far left groups like ACORN were particularly active in finding cases of alleged discrimination that they could turn into extraordinarily expensive lawsuits. In one particular case, a bank was forced to make $2.1 billion dollars available to low income borrowers who would not have otherwise qualified. Andrew Cuomo, Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Housing and Development, even admitted, “…[it] will be a higher risk. And I’m sure there will be a higher default rate on those mortgages than on the rest of the portfolio.” (4) Wow, how compassionate of Mr. Cuomo. To paraphrase, in my own, sarcastic words, “We’re going to set poor people, who should be trying to save, up to fail by forcing other people to lend them money.” In the end, the common, “blame deregulation,” chants are rather ridiculous since just about every new policy enacted was to prop up housing, and almost explicitly NOT reign in the excesses throughout the industry. As economist, Tom Woods puts it: “We are supposed to place our hopes in regulators who would have to be courageous enough to stand up to against the entire political, academic and media establishments? What regulator would have done anything differently, or dared to tell the regime something other than what it obviously wanted to hear?” (5) So nearly every factor imaginable was pushing capital into the housing market. But where did all this money to put into real estate come from? Many haven’t even asked this question. The main reason, I believe, is that people do not properly understand real estate appreciation. Realtors and bankers often said during the run-up, “real estate prices always go up” and “think of your home as an investment.” In other words, think of a house like you would a stock. If the company becomes more profitable, the stock goes up in value. Real wealth has been created. No one will admit it, but the implied assumption was that when housing prices went up, wealth was being created. Somehow just about everyone, including myself, actually thought houses were becoming more “profitable” just by their mere existence. Houses do not become more “profitable” just by sitting there, though. They may become more valuable because of factors relating to supply and demand, but as houses get older and more worn down, they should actually depreciate. Real estate appreciation is accurately defined as anything that increases the value of a house. This could be adding an addition, remodeling the bathroom, putting in a swimming pool, etc. These types of activities add real wealth. When housing prices started to dart up around the turn of the century, no new wealth was being created. No, what we saw was nothing more than plain, old inflation. Inflation was thus misinterpreted as wealth, leading American consumers to borrow more and more, especially against their overvalued homes. Total mortgage debt in the United States is now around 12.5 trillion, up from $1.5 trillion in 1980! Total household debt was around 50% of GDP in 1980 and is over 100% today. (6) And the personal saving rate was around negative 1%, for most of the last decade. (7) Add this to the federal government’s enormous 10 trillion dollar debt and we discover that the United States was basically relying solely on debt to sustain its consumption; debt that could only be maintained through the equity American’s thought their homes had. U.S. citizens were literally refinancing their homes to buy consumer products. When those homes began to depreciate, the stage was set for a significant economic contraction. So where did this inflation come from? Well, it came from the extremely foolish policy of Alan Greenspan and the Federal Reserve. Tom Woods explains their missteps as follows: “The Fed… started the boom by increasing the money supply through the banking system with the aim and the effect of lowering interest rates in the wake of September 11, which came just over a year after the dot-com bust, then Fed chairman Alan Greenspan sought to re-ignitethe economy through a series of rate cuts, culminating in the extraordinary decision to lower the target federal funds rate (the rate at which banks lend to one another overnight, and which usually drives other interest rates) to 1 percent for a full year, from June 2003 until June 2004. In order to bring about this result, the supply of money was increased dramatically during those years, with more dollars being created between 2000 and 2007 than in the rest of the republic’s history.” (8) The Fed does not directly control interest rates or the supply of money, but through what are called open market operations, the Fed can have a substantial effect on these things. The most common method it uses is to buy up bonds with money it simply create out of thin air. This adds money into the economy which, through a process called fractional reserve banking, the Fed’s initial capital injection will increase 10 fold.* The Fed can also lower the discount rate (rate at which they loan directly to banks), or decrease bank’s reserve requirements to increase the money supply. Regardless of the methods the Fed used, what is clear is that the quantity of money rapidly increased throughout the ’90’s and into this decade. The Fed uses several indicators to track the total amount of money in the economy. One of these, known as M1, increased over 100% from 1990 to 2008. M3, a more accurate depiction of the money supply, which was discontinued in 2006 because of the difficulty measuring it, increased 150% from 1995 to 2005! (9) The Federal Reserve went way overboard in an attempt to stave off a severe recession in 2001. We still had one, but it was brief and mild. In essence, they delayed much of the pain we should have faced then until now. It should also be noted, that the 2001 recession was the only recession on record in which housing starts did not decline. This should have been a sure fire sign that something was amiss in the housing market. As Peter Schiff so fittingly put it, “George Bush, in one of his speeches, said that Wall Street got drunk… But what he doesn’t point out is where did they get the alcohol? Obviously, Greenspan poured the alcohol…” (10)

To summarize, the Federal Reserve dramatically lowered interest rates, thereby increasing the quantity of money in the economy. That money had to go somewhere and due to a host of government policies and political pressure, this money primarily found its way into housing. The dangerous combination of loosened regulation and the moral hazard of deposit insurance, as well as an implicit bailout guarantee, made banks feel more and more comfortable making loans to less and less credit-worthy borrowers. With securitization, Fannie Mae, other GSE’s and banks were able to sell off their overvalued debt to unsuspecting investors, thereby infecting the entire economy. When adjustable rate mortgages began adjusting, the least credit-worthy borrowers began defaulting on their mortgages, causing home prices to fall. As home prices fell, homeowners lost their equity and could no longer refinance, thereby causing more foreclosures. As foreclosures spiked, investors and banks holding these mortgage backed securities, as well as insurance companies such as AIG who backed them, began taking massive losses. Massive losses on Wall Street meant firms had to lay-off workers. And without the ability to refinance, homeowners had less money to spend causing firms outside of finance to become less profitable and either go out of business or downsize. Thus, a mortgage meltdown turned into a financial crisis and culminated in a severe recession. Hopefully, we’ll learn the right lessons from the whole mess. Unfortunately, I kinda doubt it. _______________________________________________________________________________ *Fractional reserve banking is when a bank only has to keep a certain percentage of their deposits on hand and can loan out the rest. Typically, banks only have to keep 10% of deposits on hand and can lend out the other 90%. That 90% is then deposited in another bank, which loans out 90% of the original 90% and so on. Eventually, assuming a 10% reserve requirement, the initial deposit will increase by a multiple of 10. Mathematically it looks like this: X = Initial Deposit Y = Reserve Requirement X/Y = Total Amount of money added to the economy So for example, if you deposit $100 at a bank that has a 10% reserve requirement: $100/0.1 = $1000 will be the total amount of money eventually created. _________________________________________________________________________________ (1) “United States presidential election 1928” and “United States presidential elcction 1932,” Wikipeda.org, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_presidential_election,_1928and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_presidential_election,_1932 (2) “Shocking Video Unearthed Democrats in their own words Covering up the Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac Scam that caused our Economic Crisis,” Retrieved May 31, 2008, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_MGT_cSi7Rs (3) Peter Schiff, Crash Proof, Pg. 126, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Copyright 2007 (4) “EVIDENCE FOUND!!! Clinton administration’s “BANK AFFIRMATIVE ACTION” They forced banks to make BAD LOANS and ACORN and OBama’s tie to all of it!!!,” Retrieved May 31, 2008, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivmL-lXNy64 (5) Thomas Woods, Meltdown, Pg. 29, Regnery Publishing, Inc., Copyright 2009 (6) “Consumer Debt Outstanding” and “Household Debt% of GDP,” PrudentBear.com, both uploaded 2/28/2009, http://www.prudentbear.com/index.php/consumer-debt and http://www.prudentbear.com/index.php/household-sector-debt-of-gdp (7) “Our Savings Rate Is (Still) Negative: Should We Worry,” My Money Blog, 2/4/07, http://www.mymoneyblog.com/archives/2007/02/our-savings-rate-is-negative-should-we-worry.html (8) Thomas Woods, Meltdown, Pg. 26, Regnery Publishing, Inc., Copyright 2009 (9) “Series: M1, M1 Money Stock” and “Series: M3, M3 Money Stock (DISCONTINUED SERIES),” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M1 and http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M3 (10) Peter Schiff, “Why the Meltdown Should Have Surprised No One,” The 2009 Henry Hazlitt Memorial Lecture, Retrieved May 31, 2008, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EgMclXX5msc This is an old article on the 2008 financial crash that I wrote for Swifteconomics.com, which is now sadly defunct, that I would like to repost here. Hope you enjoy:

The financial crisis has long since turned into a severe recession, having just reached its 17th month. Unemployment reached 8.9% in May and, despite recent upticks, the stock market remains in the tank. Why did this happen? A whole host of explanations have been given, from across the political spectrum. However, by far and away the most common is the relaxed lending standards in the mortgage market, which caused a housing bubble, collapsing the financial system in upon its deregulated self. In this first part of my multi-part series on the financial crisis, I will evaluate this claim. Did deregulation cause our economy to collapse? The answer is, well kinda. Often, when deregulation is blamed, no specifics are given. In Barack Obama’s inauguration speech he only said, “…this crisis has reminded us that without a watchful eye, the market can spin out of control.” (1) When specifics are given, the finger is usually pointed at the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which overturned much of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Gramm-Leach-Bliley effectively eliminated barriers between investment banks, commercial banks and insurance companies. The idea behind keeping these institutions separate was to prevent conflicts of interest when evaluating risk. The lack of these barriers is blamed for some of the rampant speculation in the housing market. Others point to a general lack of regulation in the mortgage industry. Most banking institutions gave what were called “stated income” loans. In essence, you told the bank how much money you made, they would take your word for it without a second thought,and give you several hundred thousand dollars to buy a home with. Since shockingly, people are not always honest, this put many homeowners in loans they could not afford. This also created the dreaded NINJA loan (No Income No Job No Assets). NINJA’s are typically bad at making their payments. A lack of regulation is also blamed for allowing adjustable rate mortgages to become commonplace, especially in the sub-prime market. These loans would start out with a teaser rate and then, after a year or two, adjust to a much higher rate. When real estate was appreciating, this was fine, the homeowner could simply refinance. Unfortunately, once real estate began to depreciate, many homeowners found themselves unable to pay the increased mortgage payments, and without enough equity to refinance. All of this makes a pretty compelling argument; however, it’s missing some key ingredients. First of all, there is already a lot of regulation. There’s a ridiculous amount of regulation in fact. As Austrian economist, Tom Dilorenzo clarifies, “…we have 15 cabinet departments devoted to regulating different aspects of the economy. There are over 100 federal regulatory agencies. There are 73,000 pages of regulations in the federal register. And not to mention state and local governments that have hundreds and hundreds more regulatory agencies that regulate everything from zoning to anti-trust, to everything else.” (2) Furthermore, the housing market was not only not deregulated, it was often regulated in the opposite direction. Many government programs (such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Community Reinvestment Act, all to be discussed further in part 2) put as much pressure as possible on lenders to increase the availability of credit. All with the goal of creating what George Bush called, “an ownership society.” If there still was a lot of regulation, what exactly are we blaming? What does deregulation even mean? Deregulation should mean to remove all government barriers from any given industry. However, whether they know it or not, this is not what anyone is referring to when they say “deregulation.” Unfortunately, the term “deregulation” is basically useless now. Let’s look back to the Enron debacle, which was also blamed on deregulation, to see how this misunderstanding plays out. Nobel Laureate, Paul Krugman, professed that Enron’s illegal behavior in California, which lead to rolling black outs, was caused by “…an attempt to give market forces freer rein, by deregulating the market for electricity, [which] turned into a disaster. The nature of the disaster was obscured by rigid free-market prejudices.” (3) However, what was touted as deregulation was nothing of the sort. As journalist Timothy Carney explains: “What California tried, and Enron “gamed,” was really reregulation. It was freer than the old system, but in such a way that called for more government meddling and rules. Not only did the complex rules allow Enron to get rich, it also led to the price spikes, the energy shortages, and the blackouts that Californians suffered in 2000 and 2001.” (4) Cato Institute Scholar, Jerry Taylor elaborates further saying, “On balance, Enron was an enemy, not an ally of free markets. Enron was more interested in rigging the marketplace with rules and regulations to advantage itself at the expense of competitors and consumers than in making money the old fashioned way.” Enron took advantage of price controls and tariffs to make a mess of California’s energy market. By definition, there can be no price controls and tariffs in a deregulated market. By Taylor’s estimation, if Enron had been unable to take advantage of the strange new regulations, as well as other government support, “…Enron would probably still be a small-time pipeline company.” (5) And what was true with Enron was even more true with major mortgage institutions. There was no deregulation in the lending industry. Instead, there was simply reregulation. Lending standards were loosened some, but many regulations were kept and many more were added. Deregulation was not the problem, but the regulatory framework certainly bares much of the blame. Liberal economist, Dean Baker, describes the key problem about as well as anyone: “…Certainly most of what we’re seeing today was due to, I don’t know if I would say deregulation, I would sort of like to say misregulation of the financial sector. Because, one of the stories here is that we never really deregulated the industry fully, in the sense that the government always has been very heavily involved in the financial industry. You know, for example if you go to the bank your deposit is insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation [FDIC]. And there are many other ways in which the government is involved. The biggest way in which it is involved is what we’re seeing right now; that we have the too big to fail doctrine. That when things really go badly the government steps in and doesn’t just allow the system to collapse. And we all kind of knew that. And what is really going on is the “too big to fail” is really a form of insurance. The regulation that we put on the banks so that they don’t get involved in very speculative activities is designed, in effect, to limit the cost of that insurance". (6) Everyone knows about the massive $700 billion dollar bailout and the second bailout built upon private-public partnerships. What is important to this discussion is not that it happened, but that everyone knew it would happen before it did. The federal government has been in the bailout business for a long time. They had already bailed out Long Term Capital Management during the Asian Financial Crisis, bondholders in Mexico and the Savings and Loans in the 1980’s. The Savings and Loans crisis was very reminiscent of what we are seeing today. Lending standards were loosened while the FDIC continued to back deposits. Thus, the Savings and Loans made riskier and riskier loans with higher payoffs. But with these riskier loans came, well, more risk. Luckily for the lenders, it didn’t matter, because when everything fell apart, the government was there for them. That’s how it’s been and that’s how it still is. Profits are privatized and risk is socialized, which leads libertarian economist, Tom Woods, to agree with Dean Baker, that “…a mixture of liberalizing banks’ risk-taking ability while maintaining a government guarantee may be the worst of both worlds.” (7) Since the market was never completely deregulated, the housing bubble was not the result of a “free market.” Instead, it was the result of a market fettered with a new set of regulations, rather than the old set. The new regulatory framework reduced the oversight of lending standards (or didn’t address new issues, like adjustable rate mortgages), while continuing to back deposits, and with a wink and nod, let the banks know if anything went wrong, Uncle Sam would be there for them. All this leads Tom Woods to conclude: “When the moral hazard of deposit insurance is combined with the “too big to fail” mentality, which will not allow large institutions to fail, the result (a conclusion compelled by common sense and bolstered by recent research) is that banks will take on considerably more risk than they would if they were subject to market pressures.” (8) Thus lenders felt comfortable making more and more loans, to less and less suitable customers. As demand skyrocketed, housing prices soared upward in an unprecedented way. Builders took this as a sign to massively increase housing starts, thereby increasing supply. This was obviously a house of cards, and as soon as foreclosures began to spike, it all came collapsing down, creating the recession we are currently facing. Deregulation is not the proper word, but the regulatory framework was a major contributor to the crisis. It is, however, only one factor, and not the biggest one in my humble opinion. The misregulation theory by itself leaves a few key questions unanswered. Why was it the housing sector that was hit so hard? And why was there so much credit to push into housing in the first place? Well you’ll just have to wait until part 2 to find out. ___________________________________________________________________________ (1) Barack Obama, Inauguration Speech, January 20th, 2009, Trascript found athttp://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/20/us/politics/20text-obama.html?_r=1&pagewanted=2 (2) Thomas Dilorenzo, “The Great Depression: What We Can Learn From It Today,” The Mises Circle in Colorado, April 4th, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UQUMYO9zt4 (3) Paul Krugman, The Great Unraveling, Pg. 295, Norton Books, Copyright 2004 (4) Tim Carney, The Big Ripoff, Pg. 204, John Wiley and Sons Inc., Copyright 2006 (5) Jerry Taylor, "Enron Was No Friend of the Free Market," Wall Street Journal, January 21st, 2002 (6) Dean Baker, Interview with Mind Over Matters, KEXP 90.3 in Seattle, Washington, TalkingStickTv, January 3rd, 2009 (7) Thomas Woods, Meltdown, Pg. 47, Regnery Publishing Inc., Copyright 2009 (8) Ibid., Pg. 46

Neocons are a group that virtually no one likes. Indeed, I've never met a single person who identified as one. In fact, I've never met a single person who knew what neocon was and didn't outright hate them. Part of that is probably because they are a bunch of warmongers who are always wrong about everything. But they do, unfortunately, have a wildly disproportionate amount of influence in Washington.

As far as being wrong about everything goes, Bill Kristol is the all-time champion. Here's a very short list. But they include; Obama didn't stand a chance in the 2008 election, echoing that the insurgency was in its last throes, that Iraq wasn't in a civil war, that Trump would pick Christie as his running mate and on and on and on. But this one from before the Iraq war started is truly legendary:

Unfortunately, the Twitter handle "Kristol in History" is now inactive. But if you're looking for a good chuckle, it's worth reading through a few:

Trump's approval rating now sits at 45 percent, far above the low 30's he was at around a year ago. It's almost as if wildly over-the-top hyperbole isn't an effective method of persuasion. Sometimes I think that I would rather despise Donald Trump if it weren't for the fact the Left and most of the media were so ridiculously anti-Trump. It makes me want to root for the guy.

That being said, Trump was obviously lying about the whole "I meant to say wouldn't" thing. Some of his lies are just plain weird.

Here I discuss the ends and outs of the BRRRR method of investing (Buy, Rehab, Rent, Refinance, Repeat) and answer questions about when to flip and when to hold, how to assess the ARV (After Repair Value) of a property, how to find good contractors and what seasoning means. Enjoy!

And check out my main article on the BRRRR method here.

This article was published at the Data Driven Investor.

Empathic design is a product design method first developed by Dorothy Leonard and Jeffrey Rayport in The Harvard Business Review. The method outlines a five-step process for designing customer-focused products:

The method is similar to that used by cultural anthropologists insofar as it avoids the traditional method of simply asking customers what they want or think by actually going to them to observe them in their natural habitat. In a way, it borrows from the likes of Jane Goodall and her extended observations of chimpanzees in their natural environment. In this case, however, it is consumers in their natural environment that are to be observed and learned from. Indeed, some companies have actually hired anthropologists for these observations. This method removes many of the problems that traditional approaches such as surveys, focus groups and laboratory experiments have. Some of those problems include:

As Leonard and Sax put it, “At its foundation is observation—watching consumers use products or services. But unlike in focus groups, usability laboratories, and other contexts of traditional market research, such observation is conducted in the customer’s own environment—in the course of normal, everyday routines. In such a context, researchers can gain access to a host of information that is not accessible through other observation-oriented research methods.” In a focus group, for example, a customer may say that a given product works just fine. But when observing that person in real life, one may notice that it’s very difficult to assemble, or that the customer has created a work-around to a given problem that takes extra time, or that many of the features are never used. There are an endless number of issues that may not even cross a consumer’s mind when they are simply asked about various products. Leonard and Sax again note that, “…Customers are so accustomed to current conditions that they don’t think to ask for a new solution—even if they have real needs that could be addressed.” Indeed, it should be noted that many products we commonly used today were not invented for their given purpose. Some examples include:

On the other hand, some products looked good on paper, but never caught on because of a lack of consumer demand. The Segway is a good example of this. It was supposed to “revolutionize” walking. But had the designers spent more time with actual consumers, they would have likely found that few people considered walking to be a problem or concern. In the end, the Segway failed to find a market. The Process As noted above, the process is broken into five steps. Step 1: Observation In this step, it is critical to ask three questions:

It is important to have more than one observer, preferably from different backgrounds. Different people will notice different things and you want any preconceived biases to be “cancelled out” by others with different perspectives. Step 2: Capturing Data It’s important to record the observations so that others can view it to bring a fresh perspective and those that originally observed the consumers can review and look for details they may have missed. In the field, observers should only ask open-ended questions such as “why are you doing that?” Observers should also look for actions and not reported behavior as people often misinterpret the reasons for their own behavior. And throughout, it’s critical to, as Mathiew Turpault put it, “Treat your users like product development partners throughout the process.” Step 3: Reflection and Analysis After the field observations are complete, the team should gather to reflect on what they saw with colleagues who did not participate. Those colleagues should then ask questions to facilitate a conversation. Throughout this conversation, the goal should be to understand what exactly it is that the customer wants and needs, even if the customer is unaware of those wants and needs. Step 4: Brainstorming Brainstorming is a very useful way of collecting a large number of ideas that wouldn’t have been thought of otherwise. The key is to do it without judging ideas as they come out. Just let the process flow and then evaluate and discuss the various ideas at the end. Leonard and Sax recommend IDEO’s five rules of brainstorming (which has since been updated to seven):

Step 5: Developing Prototypes of possible solutions After the brainstormed ideas have been evaluated and a concept (or concepts) agreed upon, a prototype should be built. This prototype accomplishes three things according to Leonard and Sax:

After another round of feedback, the prototype can be improved and upgraded or perhaps discarded. This process can continue until a final product is ready for market. Examples Leonard and Sax note many examples of Empathic Design being used successfully. One involves Kimberly Clark. After some of their representatives spent time with actual customers, they realized that a pull-up diaper was sought after by both parents and toddlers for its emotional appeal. Pull-up diapers were seen as a sign of growing up. With the Empathic Design method, Cheerios realized that parents didn’t see their product primarily as a breakfast cereal but enjoyed the fact that it could be bagged and carried around. This was important for marketing purposes. Likewise, Japanese automakers have set up design studios in southern California where there are a large number of car enthusiasts who like making modifications to their cars. This has given these automakers a chance to observe them and get ideas for new features to add. Downsides to Empathic Design While there are many upsides to Empathic Design, there are some things to be cautious about. Taylor Higashi notes that “…Removed from entertainment and close personal relationships, such intimacy clouds our judgement when we attempt to make objective decisions.” Higashi references a study noted in C. Daniel Batson’s book Against Empathy where subjects were asked if they would move a terminally ill girl to the front of the line for treatment. When simply asked, they tended to not move her ahead of those who presumably were more in need. But when asked to imagine how she felt, they tended to move her up the list. Sometimes, it’s better to be removed from a subject when evaluating it. That being said, this will generally only be a problem with regards to particularly emotional situations and problems. Conclusion The Empathic Design method is a great way to create customer-centered products that the customer actually wants or needs. Often people don’t even know what they want or need. Who would have thought to want the car? Or the television? Or the Internet? In most instances, observing consumers in their natural environment is a highly effective method to inspire ideas for how to better serve those consumers.

Here is my interview with Abhi Golhar from ThinkRealty Radio on different strategies to get started in buy and hold real estate investment as well as tips on finding financing and tenants:

You can also check out my articles for ThinkRealty here as we as look for my article in the most recent edition of ThinkRealty Magazine.

|

Andrew Syrios"Every day is a new life to the wise man." Archives

November 2022

Blog Roll

The Real Estate Brothers The Good Stewards Bigger Pockets REI Club Meet Kevin Tim Ferris Joe Rogan Adam Carolla MAREI 1500 Days Worcester Investments Just Ask Ben Why Entrepreneur Inc. KC Source Link The Righteous Mind Star Slate Codex Mises Institute Tom Woods Michael Tracey Consulting by RPM The Scott Horton Show Swift Economics The Critical Drinker Red Letter Media Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed